Psychological Facts About Human Behaviour: Explained & Analyzed

Psychological facts about human behaviour provide fascinating insights into why we think, feel, and act the way we do.

These facts, gleaned from extensive research, reveal the hidden workings of our minds and help us understand the subtle and not-so-subtle forces that shape our daily lives.

From our social interactions to our personal habits, these psychological phenomena are constantly at play.

Understanding these psychological facts about human behaviour can improve our self-awareness and our ability to navigate the complexities of social dynamics.

16 Psychological Human Behaviour Facts

-

The “Spotlight Effect”

-

Explanation:

This is one of the most relatable psychological facts about human behaviour. The “spotlight effect” is the phenomenon in which people tend to overestimate the extent to which their actions and appearance are noticed by others. We feel as though we are constantly under a spotlight, and that our flaws or minor mistakes are glaringly obvious to everyone. This is often an illusion.

-

Example:

Imagine you give a presentation at work and you stumble over a few words. You might spend the rest of the day replaying that moment in your head, convinced that your colleagues are all thinking about how poorly you spoke. In reality, most of your colleagues were likely focused on their own work, their own anxieties, or the content of your presentation, not your minor verbal slip-up.

-

-

The “Halo Effect”

-

Explanation:

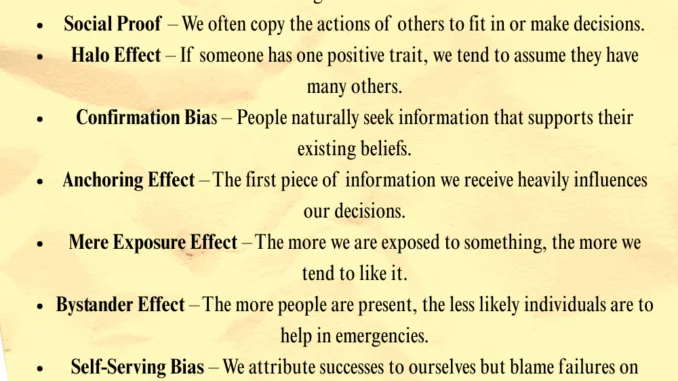

The “halo effect” is a cognitive bias in which a person’s positive first impression (e.g., attractiveness, kindness, or intelligence) “spills over” to influence our overall perception of them. This psychological fact about human behaviour suggests that our brains take shortcuts, using one or two prominent positive traits to create a generalized positive assessment of an individual. The opposite, a “horns effect,” can also occur with negative traits.

-

Example:

You meet a new person at a party who is incredibly articulate and well-dressed. You immediately assume they must be smart, successful, and kind. You might be more inclined to trust their opinions on a topic they know little about, simply because the “halo” of their initial positive traits has influenced your overall judgment.

-

-

Loss Aversion

-

Explanation:

This psychological fact about human behaviour states that the pain we feel from a loss is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure we feel from an equivalent gain. This means we are often more motivated to avoid losing something we already have than we are to gain something new. This bias is a key component of behavioral economics.

-

Example:

A classic experiment shows this perfectly. People are given a coffee mug and then offered the chance to sell it for a certain amount. A different group is offered the chance to buy the same mug. The people who own the mug consistently demand a much higher price to part with it than the people who don’t have it are willing to pay for it. The fear of losing the mug outweighs the desire for the money.

-

-

Cognitive Dissonance

-

Explanation:

Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort experienced by a person who holds two or more contradictory beliefs, values, or ideas. To reduce this discomfort, people will often change one of their beliefs to align with their behavior. This powerful psychological fact about human behaviour explains why people sometimes seem to hold irrational beliefs; it’s a way of protecting their self-image and feeling consistent.

-

Example:

A person who is a staunch environmentalist buys a gas-guzzling SUV because they need the space for their family. This creates dissonance. To resolve it, they might rationalize their purchase by telling themselves, “The car is safer for my family,” or “I need to drive this car, but I’ll make up for it by recycling more.” They are changing their beliefs to align with their actions.

-

-

The Bystander Effect

-

Explanation:

This famous psychological fact about human behaviour describes a phenomenon where individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when other people are present. The probability of help is inversely related to the number of bystanders. This is due to a “diffusion of responsibility,” where each person feels less accountable because they assume someone else will intervene.

-

Example:

A person collapses on a busy sidewalk. Instead of one person immediately calling for help, a crowd forms. Each person in the crowd thinks, “Someone else has probably already called 911,” or “I don’t need to do anything, because there are so many people here.” As a result, no one acts, and the victim is left unaided for longer than they would be if only one person was present.

-

-

The Mere-Exposure Effect

-

Explanation:

The mere-exposure effect, sometimes called the familiarity principle, is a psychological fact about human behaviour where we tend to prefer things or people that we have been exposed to more often. The more we see or hear something, the more we like it. This effect is powerful and can be subconscious.

-

Example:

You might not be a fan of a particular pop song the first time you hear it on the radio. However, after hearing it dozens of times, you find yourself humming along and even starting to enjoy it. The repeated exposure has made the song more familiar and therefore, more likable.

-

-

The Reciprocity Principle

-

Explanation:

This principle is a cornerstone of social psychology and a fundamental psychological fact about human behaviour. It states that we feel a strong social obligation to return a favor. When someone does something nice for us, we feel a powerful, often subconscious, need to do something in return.

-

Example:

A waiter brings a small candy or mint with the check at the end of a meal. Studies have shown that this small, free gesture significantly increases the size of the tip, even though the candy itself has minimal value. The customers feel a social pressure to reciprocate the “gift” with a larger tip.

-

-

The Anchoring Effect

-

Explanation:

The anchoring effect is a cognitive bias where an individual’s decision-making is influenced by the first piece of information offered. This initial piece of information, or “anchor,” then serves as a reference point, and subsequent judgments are made by adjusting from that anchor. This is a crucial psychological fact about human behaviour for understanding negotiation and marketing.

-

Example:

A new car is listed with a sticker price of $50,000. Even if you negotiate the price down to $45,000, you feel like you got a great deal. The initial, high “anchor” price of $50,000 made the lower price seem like a significant discount, even if the car’s true market value is closer to $40,000.

-

-

Procrastination as a Form of Emotional Regulation

-

Explanation:

This is a more modern understanding of a common psychological fact about human behaviour. Procrastination is often not a result of laziness or poor time management, but a way to avoid or cope with negative emotions associated with a task, such as boredom, anxiety, insecurity, or frustration. By delaying the task, we get a temporary relief from those feelings.

-

Example:

A student has a massive paper due and feels overwhelmed and anxious about starting. Instead of beginning the research, they decide to clean their entire apartment, binge-watch a TV show, or scroll through social media. These activities provide a temporary emotional escape from the stress of the impending deadline.

-

-

The Zeigarnik Effect

-

Explanation:

The Zeigarnik Effect is the tendency to remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than completed ones. This psychological fact about human behaviour is based on the idea that our minds create a “task-specific tension” when we begin an activity. This tension is released only upon completion, which is why we think about unfinished business more.

-

Example:

You are watching a TV show, and the episode ends on a dramatic cliffhanger. You are more likely to remember that specific episode and think about it until the next one airs. The unresolved plotline creates a mental “hook” that keeps the story active in your memory.

-

-

The “Curse of Knowledge”

-

Explanation:

This psychological fact about human behaviour describes a cognitive bias that occurs when a person, communicating with others, unknowingly assumes that the others have the background knowledge to understand. The expert has a difficult time imagining what it is like not to know something.

-

Example:

A programmer is explaining a technical concept to a non-technical colleague. They might use a lot of jargon and assume their colleague understands the fundamental principles. The colleague, in turn, is completely lost, but the programmer can’t understand why, because the concepts seem so basic to them.

-

-

The Power of Social Proof

-

Explanation:

Social proof is a powerful psychological fact about human behaviour where people assume the actions of others reflect the correct behavior for a given situation. We look to the people around us to help us decide what is right, especially in situations where we are unsure how to act.

-

Example:

You are walking down a busy street and see a restaurant with a long line out the door. You immediately assume the food must be excellent, even though you have no other information about it. A nearby restaurant that is empty, in contrast, is assumed to be inferior. You use the behavior of the crowd as a signal for quality.

-

-

The “Placebo Effect”

-

Explanation:

The placebo effect is one of the most fascinating psychological facts about human behaviour. It describes the phenomenon where a person experiences a real, measurable improvement in their condition after receiving a “placebo” treatment (a sham treatment with no active ingredients). The patient’s belief that the treatment will work is what causes the positive change.

-

Example:

A group of people with headaches are given a sugar pill, but they are told it’s a new, powerful painkiller. Many of them report that their headaches go away, not because of the sugar, but because their mind’s expectation of relief triggers a real physiological response.

-

-

The “Peak-End Rule”

-

Explanation:

This psychological fact about human behaviour explains how we judge an experience. We don’t judge it by the average of all its moments. Instead, we form our memory and our overall evaluation based on how we felt at the most intense part (the “peak”) and at the very end of the experience.

-

Example:

You go on a week-long vacation. The entire trip was generally pleasant, but on the last day, you have a truly incredible meal at a restaurant, and the flight home is smooth and easy. Your memory of the entire vacation will likely be extremely positive, colored by that amazing peak and the pleasant end, even if there were some less-than-perfect moments in the middle of the week.

-

-

Confirmation Bias

-

Explanation:

Confirmation bias is a pervasive psychological fact about human behaviour where we tend to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports our prior beliefs. We actively avoid information that contradicts our views. This leads to intellectual laziness and a tendency to become more entrenched in our opinions.

-

Example:

A person who believes a certain political candidate is dishonest will actively seek out news articles and social media posts that highlight the candidate’s flaws, while completely ignoring or dismissing any positive news about them. They are confirming their pre-existing belief rather than forming a new one.

-

-

The “Primacy Effect”

-

Explanation:

This psychological fact about human behaviour is a memory bias where the information presented early in a list or sequence is recalled more easily than information presented later. Our brains pay more attention to and encode the first things we encounter.

-

Example:

In an interview, a candidate’s first answer is usually their most polished and well-rehearsed. This first impression, thanks to the primacy effect, will have a disproportionate influence on the interviewer’s overall judgment of the candidate, regardless of the quality of the answers that follow.

-

Conclusion

The study of psychological facts about human behaviour offers a rich tapestry of knowledge that helps us understand ourselves and others more deeply.

These phenomena—from the subtle biases that color our judgments to the powerful social forces that shape our actions—are not merely academic curiosities.

They are the gears and levers of our daily lives. By recognizing these psychological facts about human behaviour, we can gain a clearer perspective, make more informed decisions, and develop greater empathy for those around us.

Be the first to comment